Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is far more common than you think, and chances are you may have experienced it at some point in your life.

On average, half of the U.S. population will experience at least one severely traumatic experience in their life. About 8% of the total population will develop some form of PTSD because of either directly being subjected to trauma or having witnessed it.

In any given year, more than 8 million adults will be suffering from PTSD.

That’s a lot of people.

As we wrap up Mental Health Awareness Month, we are going to talk about what PTSD is, how your brain copes with trauma and the things we can do to treat it. If you think you may be suffering from PTSD, you are not alone.

Weirdly, PTSD is the result of your brain trying to protect you from danger.

What is PTSD?

Weirdly, PTSD is the result of your brain trying to protect you from danger. When you are in a situation where you feel that you are under threat, your brain activates your sympathetic nervous system. You may have heard this referred to as a fight or flight response. This system tells your body to prepare itself to escape whatever is threatening you:

- Adrenaline hormones course through your body, telling your muscles and organs that you are getting ready to experience a demanding physical ordeal.

- Your heartbeat increases to pump more blood through your arteries so that your muscles have enough oxygen to run from what is threatening you.

- You begin to sweat so that your body can keep cool as it exerts itself.

The problem is nothing is chasing you and nobody is attacking you. You may be alone and perfectly safe yet feel as if your life is in imminent danger.

This sensation can envelop you without warning and at any time. There is no hiding from it.

You begin to panic, scream, lash out, and cry…

You are in a fight for your life – at least that is what your brain is telling you.

Your brain is trying to protect you from danger, but it has become a little confused about when that danger was an actual threat.

People who suffer from PTSD are constantly reliving their ordeal of trauma, trying desperately to outrun terrifying memories that they cannot figure out how to escape.

The Effects of PTSD on the Brain

When you experience trauma, certain memories can be filed away in long-term storage to help remind you to never repeat that experience. It’s a survival mechanism.

Sometimes the brain overreacts, and you may end up experiencing those memories many times over. Even though you are not in any real danger, your brain is unable to tell the difference between a real and a perceived threat.

PTSD has a dramatic effect on the Limbic system of your brain which is responsible for long-term memory formation as well as fear learning and emotional response. While several structures comprise the Limbic system, the amygdala is the structure thought to be responsible for activating fearful and anxious emotions. Under situations of extreme stress, terror, or shock the Limbic system can become too active and store fear responses in long-term memory which hinder the quality of life and social connections with others.

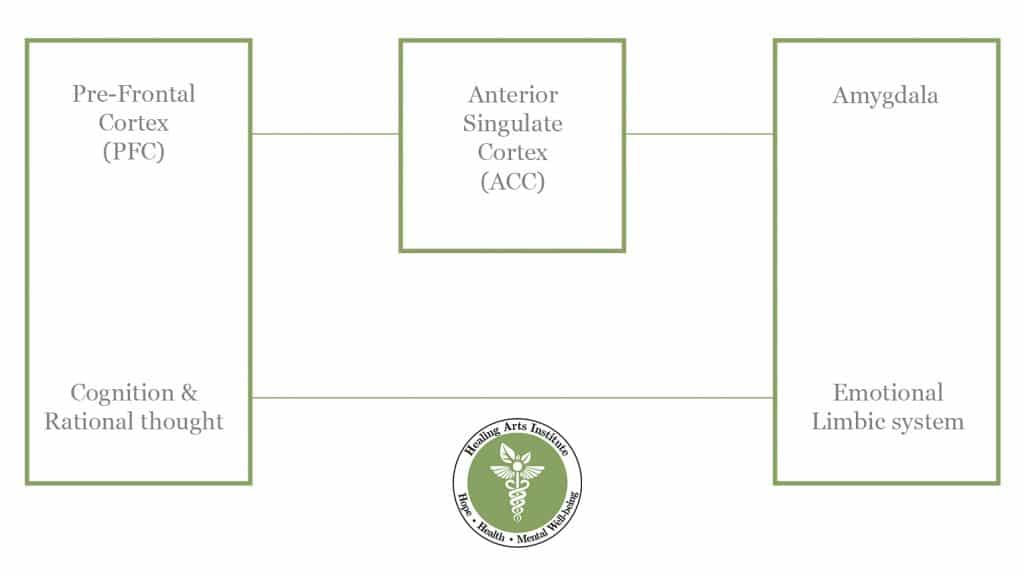

A part of your brain which normally helps to regulate and calm the Limbic system is called the Pre-Frontal Cortex (which we’ll abbreviate as PFC). This part of your brain is responsible for rational thought and is generally able to tone down the activation of your amygdala. In a neurotypical brain, these two structures balance one another, but in a PTSD brain, the emotional Limbic system runs rampant.

Interestingly, a third structure is involved in emotional regulation which connects to both the amygdala and the PFC. It’s called the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC). It can influence emotional regulation depending on which neural system has more influence.

In other words, the ACC can help your rational-thought processes regulate the Limbic system if your PFC has strong functional connections to it. But it also means that the opposite is true. If your over-active amygdala develops atypical functional connections to the ACC, it can be more difficult to regulate emotions.

The altered performance of functional connections from the amygdala to the ACC has been observed extensively in at-risk youth. Many of these kids experience violence at home and at school, which over time instills long-term fear learning and the development of PTSD.

Who is Susceptible to PTSD?

Anyone who has personally experienced or who has witnessed a terrifying and traumatic event can develop post-traumatic stress disorder. People who are subjected to consistent stress over long periods can also develop PTSD even if they have never faced a particularly shocking event that is normally associated with trauma.

Victims of child abuse and domestic violence often describe symptoms and show signs of PTSD from long-term and sustained stress.

Some people who suffer from PTSD describe feeling guilty that their suffering is not worth the time and attention to treat. They compare their experiences with the experiences of others and decide that their trauma is not worthy of recognition.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Trauma is very personal. If it matters to you, then it matters. Period. You should never feel as if you must justify that to anyone, not even to yourself.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to the Rescue

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a treatment method that engages the rational thought structures of your brain to overcome and regulate your emotions. Remember the Pre-frontal cortex (PFC) that we talked about earlier? It teaches you how to think through your thoughts and emotions in a logical and structured way rather than remaining subservient to emotions and fear.

When your PFC makes strong connections with the ACC and Limbic system, it becomes easier to overcome and control the irrational fear responses of PTSD. This takes time and a lot (and I mean a lot) of practice.

Some medications can help ease symptoms, but medication alone is not a cure. Medical studies have shown that a combination of medication and CBT in treating PTSD is far more effective than either one alone.

Overcoming PTSD is a long and hard road, but with the help and guidance of a trained therapist, anyone can learn to control and even defeat their PTSD symptoms.

Citations:

American Psychological Association. “Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults.” American Psychological Association, Mar. 2017, www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/cognitive-behavioral-therapy.

Gold, Andrea L et al. “Amygdala-prefrontal cortex functional connectivity during threat-induced anxiety and goal distraction.” Biological psychiatry vol. 77,4 (2015): 394-403.

Marusak, H., Thomason, M., Peters, C. et al. You say ‘prefrontal cortex’ and I say ‘anterior cingulate’: meta-analysis of spatial overlap in amygdala-to-prefrontal connectivity and internalizing symptomology. Transl Psychiatry 6, e944 (2016).

“Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – Symptoms and Causes.” Mayo Clinic, 6 July 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967.

Stevens, Francis, et al. “Anterior Cingulate Cortex: Unique Role in Cognition and Emotion.” The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, vol. 23, no. 2, 2011, pp. 121–25. Psychiatry Online, neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121.

“VA.Gov | Veterans Affairs.” U.S. Deprtment of Veteran’s Affairs, 2021, www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp.

“What Is PTSD?” American Psychiatric Association, 2020, www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd.

No responses yet